The historical controversy on where the 1521 Easter Sunday Mass (previously called “First Mass”) was held has been affecting generations of Filipinos.

NOTE: This is just a digest of the Mojares Panel report on the issue of the 1521 Easter Sunday Mass. Access the full report and related documents from the National Historical Commission of the Philippines here.

The National Historical Commission of the Philippines (NHCP) received multiple claims as to where the site of the 1521 Easter Sunday Mass was: some say it was in Masao or in Pinamanculan, both are neighboring barangays in the highly historic Butuan City; others claim it was in Baug, Magallanes, Agusan del Norte (which was the former town proper of Butuan; actually, the Spaniards erected a monument here in 1872 commemorating the “First Mass”).

Since 1921, the Philippine government recognizes Limasawa, an island municipality of the Province of Southern Leyte, as the site of the event, based on the stand of the Committee for the IV Centenary of the Discovery of the Philippines created by the U.S. Insular Government of the Philippine Islands. It was further recognized through a historical marker by the Philippines Historical Committee (forerunner of the NHCP) installed in Limasawa in 1950 and a new one on 31 March 2021 in Barangay Triana, at the west side of the island. The National Historical Institute and its successor NHCP constituted four panels to settle the historical issue (i.e., 1980 Samuel Tan Workshop, 1995 Justice Emilio Gancayco Panel, 2008 Benito Legarda Panel, 2019 Resil Mojares Panel)—all reaffirmed the historicity of Limasawa. Section 5(e) of the Republic Act No. 10086 or the NHCP Charter mandates the agency to “actively engage in the settlement or resolution of controversies or issues relative to historical personages, places, dates and events.” The recent decision of the NHCP, formalized through NHCP Board Resolution No. 2 signed on 15 July 2020, was further supported by the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of the Philippines (CBCP) through a statement of CBCP Church History Team to the Mojares Panel issued on 26 February 2021.

The Term “First Mass”

Before it constituted the Mojares Panel in November 2019, the NHCP and CBCP agreed to adopt the term “Easter Sunday Mass” to refer to the Christian mass celebrated on 31 March 1521 in the highly contentious place called Mazaua. This is to not preempt other possible Christian masses prior to 31 March 1521. This was adopted by the National Quincentennial Committee in its promotions and publications, in print and online.

Error in Reading Butuan

Note: Primary sources are firsthand accounts of those who witnessed the event or close to the event as it happened. Whereas, secondary sources were written by non-witnesses based on the narratives of firsthand accounts or by interviewing eyewitnesses; contents are verifiable by revisiting the primary sources.

For almost 300 years, Spaniards and Filipinos believed the 1521 Easter Sunday Mass happened in Butuan—not until scholars had full access to one of the four extant manuscripts of Pigafetta’s chronicle of the Magellan-Elcano expedition in 1800: the Italian text archived in the Veneranda Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan, Italy, which mentions nothing about Butuan as the site of the 1521 Easter Sunday Mass but Mazaua. In 1895, the Ambrosiana copy of Pigafetta’s was published in its original language for the first time. This gave Filipino linguist and philologist Trinidad H. Pardo de Tavera the opportunity to verify that indeed there was no mention of Butuan in Pigafetta’s chronicle and since then began recognizing Limasawa as the logical Mazaua.

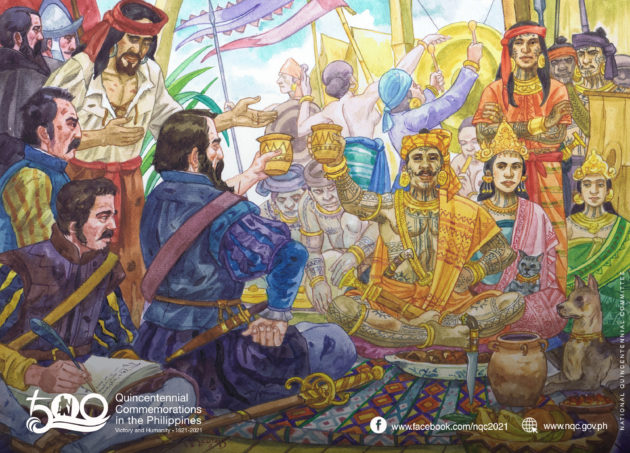

Historian Fr. Pablo Pastells, SJ, who was among the teachers of Jose Rizal at Ateneo de Municipal de Manila (now the Ateneo de Manila University), corrected his predecessor Jesuit historians and chroniclers like Fr. Francisco Colin, SJ who proliferated the error for centuries. Fr. Miguel Bernad, SJ, another Jesuit historian, traced the earliest known source of attributing Butuan as the site of the 1521 Easter Sunday to the summarized version of Pigafetta’s chronicle published in Gian Battista Ramusio’s 1550 three-volume work, Delle navigationi et viaggi (a secondary source already). Eminent Philippine historian William Henry Scott, who supported Fr. Bernad’s criticism to Butuan, observed that “Ramusio edition shows… to be a paraphrase rather than a translation—and a poor one.” It is because Ramusio confused the volunteering of Siaui, the rajah of Butuan who visited Mazaua, of bringing Magellan and Pigafetta to the Trinidad, the flagship of the expedition anchored off the island, after a feast hosted by Colambu, the rajah of Mazaua and a sibling of Siaui of Butuan. What Ramusio wrote was that Magellan was in Butuan and Siaui accompanied to Butuan Magellan’s men who were in Trinidad—and succeeding this story is already about the 1521 Easter Sunday Mass. Ramusio also garbled the characters.

Pigafetta’s Text

When dawn broke, the king (Colambu of Mazzaua—NQC) came and took me by the hand, and so we went to the same place where we had dined to partake in breakfast (in Mazzaua—NQC), but this time the small boat came to pick us up (to be brought to the flagship, Trinidad—NQC). Before we left, the king joyfully kissed our hands as we did his. A brother of his (Siaui—NQC), who was the king of another island (Butuan and Calaghan—NQC), and three of his men came to accompany us (to the flagship—NQC). The captain general kept him to dine with us and gave him many gifts.

“In the island of this king who came to our ships one can find pieces of gold, of the size of walnuts and eggs, abundantly covering the land… His island is called Butuan and Calagan.”

Ramusio’s Text

“The Prince departed at the break of dawn, but as ours were getting up, a brother of his came to find them, and they accompanied him to an island where the Captain was, who kept them to dine with them and gave many presents to him and all those with him.

“In that island where the King came to see our ship, big pieces of gold were found… These islands are called Buthuan and Calaghan.”

Ramusio’s work influenced generations of writers. But as the discipline of History develops through time, students are trained to discern what is primary from secondary and that one must put a premium to the former and be critical of the sources and provenance of the latter. With this, historians who supported Limasawa instead of Butuan have just exercised the basic historical methodology of tracing the primary source and scrutinizing its provenance vis-à-vis recognized Pigafetta over Ramusio, Colin, etc. Citing secondary sources or non-contemporaneous, non-eyewitness accounts in supporting Butuan as the site of the 1521 Easter Sunday Mass is dead-end.

Primary Sources Matter

There is this misconception that documents written during the Spanish period are considered primary sources because they are basically Spanish. Some of the Butuan proponents argued that the following Spanish sources mention Butuan as the site of the 1521 Easter Sunday Mass are valid sources: 1581 edict of Bishop Domingo Salazar in the Anales ecclesiasticos de Filipinas 1574-1683, the 1886 Breve reseña de diocesis de Cebu, Fr. Francisco Colin’s Labor evangélica: Ministerios apostolicos de los obreros de la Compaña de Jesus (1663), Fr. Francisco Combés’ Historia de Mindanao y Jolo (1667), Fray Gaspar de San Agustin’s Conquistas de las Islas Filipinas (1698), the 1872 monument in Magallanes, Agusan del Norte, and a few other accounts written by American authors in the early part of the 20th century.

There are countless non-primary or non-contemporaneous sources pertaining to Butuan as the site of the 1521 Easter Sunday Mass. But, as already said in the preceding slide, for almost 300 years, Spaniards and Filipinos believed the 1521 Easter Sunday Mass happened in Butuan—not until scholars had full access to one of the four extant manuscripts of Pigafetta’s chronicle of the Magellan-Elcano expedition in 1800: the Italian text archived in the Veneranda Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan, Italy, which mentions nothing about Butuan as the site of the 1521 Easter Sunday Mass but Mazaua. As an iteration, historian Fr. Pablo Pastells, SJ corrected his predecessor Jesuit historians and chroniclers like Fr. Francisco Colin, SJ who proliferated the error for centuries. Fr. Miguel Bernad, SJ, another Jesuit historian, traced the earliest known source of attributing Butuan as the site of the 1521 Easter Sunday to the summarized version of Pigafetta’s chronicle published in Gian Battista Ramusio’s 1550 three-volume work, Delle navigationi et viaggi (a secondary source already).

Again, citing secondary sources or non-contemporaneous, non-eyewitness accounts, where in fact there are solid primary sources available, in supporting Butuan as the site of the 1521 Easter Sunday Mass is dead-end.

Bounds of Reason

Upholding the centuries-old Butuan tradition, most of the anti-Limasawa proponents argue that the Mazaua mentioned by Pigafetta as the site of the 1521 Easter Sunday Mass was actually Masao, Butuan City. They also argued that compared to Limasawa, Masao is closer in spelling to what ‘primary sources’ mention (i.e., Mazaua). In toponomy (interdisciplinary study of the origin of place names using linguistics, history, archaeology, anthropology, geology, and geography, among others), archival spellings are not taken at face value. It is toponymically erroneous to claim that Zzamal, Humunu, and Zzubu were the ‘original’ names of Samar, Homonhon, and Cebu only because it was how Pigafetta spelled them. One can collect as many spelling variations of Mazaua from 16th-century primary and secondary sources (including maps), but these must undergo the scrutiny of toponymical methodology. It is still the descriptions of the island of Mazaua that matter.

The Mojares Panel scrutinized the coordinates of Mazaua given by the eyewitnesses and compared them with contemporary measurements. Pigafetta recorded it at 9 2/3 or 9º40’N latitude, Francisco Albo, another eye witness, placed it at 9 1/3 or 9º20’N latitude, and the Genoese Pilot, also a primary source, wrote 9 or 9º00’N latitude. The panel cited a study presented in the 16th International Multidisciplinary Scientific Geoconference (Bulgaria, 2016) by a group of experts who compared the coordinates given by Pigafetta with the present coordinates using a computer-based system and the result was 9⁰56’ N latitude or only a 0⁰16’ difference against Pigafetta’s. Even a layman can confirm the coordinates of Limasawa by simply Googling it and the result will be a 9°54’ N latitude. Taking all these pieces of evidence into account, the panel noted that, although the navigational coordinates during this period were just estimates, Pigafetta’s 9º40’N latitude was still closer to Limasawa than to Butuan which, using the modern coordinates, was located at 8°56’ N latitude.

Another argument they developed was that Masao was formerly an ancient island that eventually merged with mainland Butuan. Therefore, the arguments imply that Mazaua was closer to mainland Mindanao for a few miles. But primary sources, at least by Pigafetta, describe nothing about Mindanao, and the way Pigafetta described the island of Butuan and Calaghan, which are definitely in Mindanao, had a certain distance. Assuming that there indeed geological changes that happened between 1521 to the present, the location of Masao, Butuan City is too far from the coordinates given by Pigafetta and Albo and the current reckoning of contemporary experts.

Limasawa: The Logical Mazaua

Pigafetta noted that Mazaua was 25 leagues away from Acquada (i.e., Homonhon). Butuan is already 35.56 leagues (197.95 kms) away from Homonhon (an island in Guiuan, Eastern Samar) compare to Limasawa, which is 23.99 leagues (133.58 kms), thus, close enough to what Pigafetta had recorded. The chronicler also recorded Mazaua at 9 2/3 (9º 40’N latitude in modern reading), Albo placed it at 9 1/3 (9º20’N latitude), and the Genoese Pilot wrote 9 (9º00’N latitude). Even a layman can confirm the coordinates of Limasawa by simply Googling it and the result will be a 9°54’ N latitude. Although the navigational coordinates during his period were just estimates, Pigafetta’s 9º40’N latitude was still closer to Limasawa than to Butuan which, using the modern coordinates, is located at 8°56’ N latitude.

Ascertaining where Mazaua was is necessary to establish a very important fact: did Magellan ever touch the Mindanao soil via Butuan as early as 28 March 1521 (date of Magellan’s landing in Mazaua)? Because if so, they could have gone straight to the Maluku via the east side of Mindanao. Nevertheless, history has it that Magellan became more interested in Cebu, an island ‘northwest’ of Mazaua, upon hearing it from Colambu while in Mazaua.

Almost forty-four years after, on 13 February 1565, Miguel Lopez de Legazpi, head of the Spanish expedition to the “western islands” (later named the Philippines), requested the people of Cabalian (now the Municipality of San Juan, Southern Leyte) if someone could bring him to Mazaua. Legazpi said, “the people there were friends of the Spaniards whereas in other places we had found no friends.” According to the local people, the location of Mazaua from Cabalian “was only leagues away,” implying it was indeed nearby. For centuries, it was believed that the island of Mazaua was part of Butuan, and that later on the island became part of the Mindanao landmass owing to the siltation of Agusan River. While the said natural phenomenon is possible to occur in a delta-like the mouth of Agusan River, Mazaua should be just a few kilometers from mainland Mindanao. But how come the 1565 report implies that Mindanao is quite far from Mazaua (“that the land which they could see from that place [Mazaua] was a point of the island of Vindanao [sic]”). And if Mazaua was in Butuan, why did Legazpi have to pass by Mazaua (from Cabalian on 9 March 1565) in proceeding to Camiguin (“which they could see from there” [Mazaua] on 11 March 1565) to gather cinnamon and then to Butuan (afternoon of 14 March 1565)? From Cabalian, the distance of Butuan is 25.17 leagues (140.1 kms)—too far to be described as “only leagues away.” But Limasawa, an island municipality in Southern Leyte, which most historians think to be the historic Mazaua, is barely 7.43 leagues (41.36 kms) away from Cabalian via Panaon Strait.

—

Stay updated with news and information from the National Quincentennial Committee Philippines by visiting their website at https://nqc.gov.ph.

Images courtesy of the National Quincentennial Committee Philippines